Books have long been my best friends. I grew up barefoot in the cornfield-studded countryside with nanny goats and Jesus as my closest companions. There was no television in our house, no Saturday morning cartoons. But there were books. Shelves stuffed with garage-sale randos and my father’s collection of organic farming manuals. Archie comic books and Richard Scarry’s illustrations. My Nana’s cast-off collection of mystery and romance novels. A few Nancy Drews, a Bobbsey Twin.

Best of all there was the Dixon Public Library, a stately stone building on South Hennepin Avenue that looked like a castle to my child-size eyes. My mother would drop my sister and I there, armed with an empty apple box, and leave us to read and scavenge while she stocked up on groceries at the Eagle.

Each week, we filled that apple box to the brim with books and each week we read every single one, escaping into worlds of hobbits and centaurs and magic and mayhem.

As an adult, I have consistently spent a sizable portion of my paycheck on books. I don’t go to the library so much anymore because any book I love, I want to have and hold forever. The bulk of the boxes that crossed the Atlantic with us were stuffed with books—old friends I refused to leave behind.

I read mostly fiction, and I choose my titles carefully. I usually read stories written by women. (I spent most of my early years inundated with stories told by and about men and I am just over it. Acabo! as Filha’s teachers say when the middle school boys won’t shut up.) I want to hear what women have to say—what they’ve seen and lived and dreamed and done. There are a few titles listed below authored by men, it’s true, but only when I believe it’s truly worth it.

In addition to avoiding books by men I also avoid reality in my fiction selections, choosing instead to read about imaginary worlds and times. As I wrote recently, reality is enough of a horror show. I don’t want to read the gritty novel about an alcoholic staring through a train window or a post 9-11 scavenger hunt through NYC or a dysfunctional writer who survived a gang rape and a school shooting or any of the more “realistic” novels that usually climb the bestseller lists. I prefer alternate realities in my escapism.

When I read non-fiction, I gravitate toward poetry and memoir, and usually those memoirs and poems are written by people who are nothing at all like me. Words contain worlds, and I am constantly trying to expand my own worldview. I want to see differently, I want to unlearn and learn anew, I want to care more about people and places and paradigms I never knew existed. Books open doors to empathy and understanding. They make us ask why we think the way we see the world is the only way to see it. Open someone else’s story and you open yourself.

That’s why I read. To lose myself. Undo myself. To find myself somewhere new.

For the past week or more I’ve been combing my bookshelves, collecting the titles that really made me think or brought me joy this past year. Although I have no doubt I’ll think of more books to share the minute after I hit publish, I’ve assembled my favorites here. Consider his post my winter festivus gift to you.

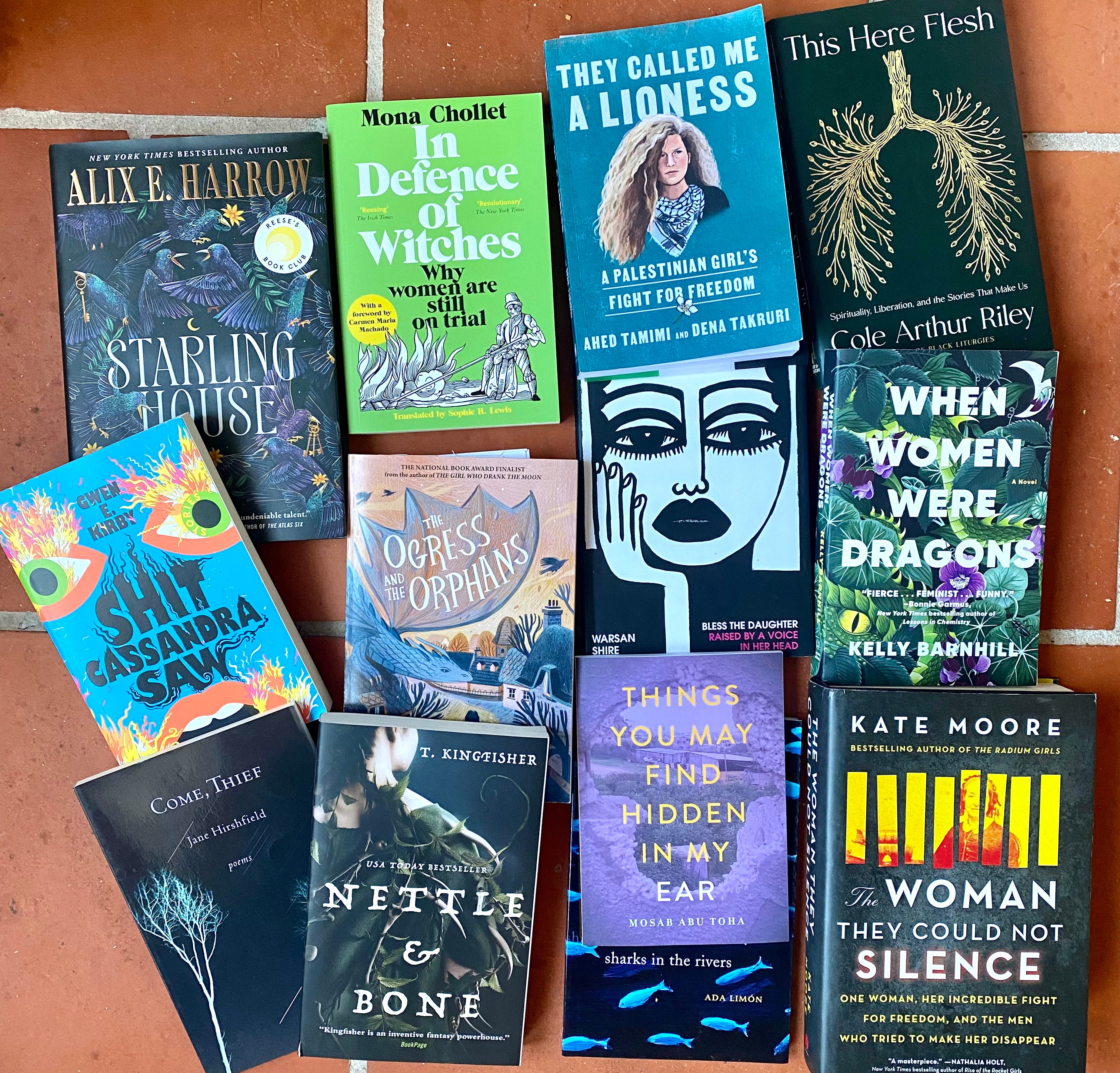

BOOKS I LOVED IN 2023…

They Called Me A Lioness by Ahed Tamimi & Dena Takruri

I have long believed that stories have the power to change the world. I’ve taught workshops and given lectures about the power of our stories, about the importance of raising our voices and owning our own narratives. So of course I was going to read Ahed Tamimi’s story. How could I not?!

Ahed is a Palestinian activist who grew up in the village of Nabi Saleh in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. When she was just 16 years old, she was arrested and dragged from her home in the middle of the night. Her crime? A viral video that showed her slapping a fully-armed Israeli soldier in the face. Ahed calls it “a slap that reverberated around the world.”

Her book, written with American/Palestinian journalist Dena Takruri, recounts Ahed’s childhood in occupied territory, her arrest and 8-month detention in an Israeli prison, and the aftermath of her release.

Just last month on November 6, the now-22-year-old law student was arrested again and held for 23 days. She was released during the pause in the ongoing bombardment of Gaza as part of the agreement for the release of hostages captured by Hamas. No charges were filed against her in the three weeks she was held. Her friend and co-author Dena said, “I’m deeply disturbed and concerned by how visibly traumatized and worn down she appears coming out of Israeli prison, where we know she was beaten.”

Ahed has become a symbol of Palestinian resistance and hope. No matter where you stand on the issue of Israel and Palestine, her memoir is a necessary read, a story that sheds light and makes you ask yourself that essential question: “If it were me, if it were my family, what would I do?”

Nettle & Bone by T. Kingfisher

Every once in a great while I run into a writer who blows the top of my head clean off. The kind of writer who makes you want to throw the book across the room because it’s just. that. good.

T. Kingfisher is that kind of writer. I bought Nettle & Bone last spring on a whim. The cover was cool, the title intriguing and I shrugged a “sure, why not” and cracked it open. The first sentence slapped me straight across the face:

The trees were full of crows and the woods were full of madmen. The pit was full of bones and her hands were full of wires.

Ummm, ok, Holy Shit Wow, keep going. It was the dogs she wanted. Perhaps she might have built a man out of bones, but she had no great love of men any longer. Dogs, though… dogs were always true.

What even IS this book?! Marra caressed the hollow orbits, delicately winged in wire. Everyone said that the heart was where the soul lived, but she no longer believed it. She was building from the skull downward. She had discarded several bones already because they did not seem to fit with the skull. The long, impossibly fine ankles of gazehounds would not serve to carry her skull forward. She needed something stronger and more solid, boarhounds or elkhounds, something with weight.

There was a jump rope rhyme about a bone dog, wasn’t there? Where had she heard it? Not in the palace certainly. Princesses did not jump rope. It must have been later, in the village near the convent. How did it go? Bone dog, stone dog…

The crows called a warning.

That’s it, that’s all I’m giving you, you just have to go get the book and read the rest yourself. I’m just warning you that if you start down the T. Kingfisher road, you might end up like me… having combed the universe for every scrap she’s ever written and inhaled them all: Thornhedge and The Clockwork Boys and Paladin’s Grace and What Moves the Dead and House with Good Bones and The Hollow Places and The Twisted Ones and A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking even all the middle-school novels she wrote under the pen name Ursula Vernon, books that even now lie wrapped in festive paper under the tree waiting for Filha to find.

If you don’t start with Nettle & Bone, I’d like to recommend my other favorite title of hers, a book of short stories called Jackalope Wives that will melt your face off. In the best kind of way. Kinfisher’s protagonists are never who you think they’re going to be, they never do what you think they’re going to do and that’s one of the reasons why I love them so.

Starling House by Alix E. Harrow

Alix is another one of my favorite fiction writers, and her book The Once & Future Witches will always be in my Top 10. She came out with a new novel this year that is, as one reviewer put it, “an amazing bit of spellcraft.” I’ll give you a taste from Chapter One, but I warn you that you’re going to be left wanting more:

I dream sometimes about a house I’ve never seen.

I mean, pretty much nobody has. Logal Caldwell claims he ding-dong-ditched the place last summer break, but he’s an even bigger liar than me. The truth is you can’t really see the house from the road. Just the iron teeth of the front gate and the long red lick of the drive, maybe a glimpse of limestone walls crosshatched by honeysuckle and greenbriars. Even the historical plaque out front is half-swalled by ivy, the letters so slurred with moss and neglect that only the title is still legible: STARLING HOUSE.

But sometimes in the early dark of winter you can see a single lit window shining through the sycamores.

When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill

I don’t have enough words to tell you how much I love Kelly Barnhill’s writing. I know I said that about T. Kingfisher and Alix E. Harrow, and I was not lying. Kelly joins them on my shortlist of Fiction Goddesses At Whose Feet I Gladly Worship Forever and Ever, Amen.

Kelly has written so many great books: The Girl Who Drank the Moon and The Witch’s Boy and Iron Hearted Violet and Mrs. Sorensen and the Sasquatch. But this one, THIS ONE is close to my heart. For one thing, it’s about dragons and if you know Filha at all, you will know that she loves dragons, has been obsessed with dragons since she started reading Wings of Fire in second grade. For another thing, it’s about women who feel stifled and suppressed and restricted from being their whole, true selves, and that story is like my life story in some ways, and is all wrapped up in my religious upbringing and so Hot Damn! I was just pre-destined to love this book. And then there’s the Barnhill factor in which Kelly is just such a mind-blowing writer.

I wish I hadn’t already read this book only so I could discover it and read it for the first time all over again!

Spare by Prince Harry

I am by no means a fan of the British monarchy. Other than Princess Diana, who was everywhere when I was growing up, I have paid them little mind. But when Meghan Markle entered the scene in 2016, I started paying more attention. Maybe because she was American, maybe because she was a bi-racial woman and I was curious about how the lily-white Windsors would react to her presence. Even though I wasn’t exactly optimistic, I have been shocked at how blatantly they have wronged her. As she and Prince Harry left the UK behind and sought refuge first in Canada and then the States, I began to notice something peculiar in interviews I saw and read. I began to notice marked similarities between Harry’s exodus from his royal family and my own exodus from fundamentalist religion. It gave me a massive amount of empathy for him, and when his memoir was published I was curious to give it a read.

Within a few sentences of embarking on the book, I could tell he had a ghost writer who knew his way around wordcraft. “Good,” I thought, “Good that his story will be told capably and well.”

Spare was a quick and enjoyable read and I’m glad I read it immediately after its release instead of being spoiled by endless excerpts and opinions from everyone everywhere. I maintain my sympathy and empathy for the Prince and the family he and Meghan have created and I hope for him a thorough and healing deconstruction from his royalist upbringing and all the harm and hullabaloo contained therein.

All My Rage by Sabaa Tahir

On the surface, this novel is all about young love. But underneath the plot it plumbs the depths of old regrets. From Lahore, Pakistan to Juniper, California, this story is tragic and poignant and tender and fierce and I absolutely loved it.

I had read Sabaa’s work before in the form of her Ember in the Ashes series, which I enjoyed. But All My Rage is on another level altogether, and absolutely deserves all the accolades Sabaa has earned in the wake of its publication.

In interviews promoting the book, Sabaa said her own experience growing up as a Pakistani-Muslim girl in a predominantly white desert town shaped the way she told this story. That lived experience is evident in the richness of her storytelling and the depth of feeling you can sense on every page.

The Suicide Index by Joan Wickersham

In my quest to write my own memoir, I’ve read lots and lots and lots of memoirs, studying storytelling and form and structure. This memoir employs a radical departure from the usual narrative form, and it works incredibly well.

Joan examines her father’s suicide by structuring the memoir as a literal index—Suicide: act of, anger about, attitude toward.

In interviews, Joan says that writing the book was an 11-year process. She was 33 in 1991 when her father killed himself. She wrote the first piece connected to his death in 1995 and completed her memoir in 2006. It was published two years later.

“I worked on it as a novel for about eight years,” she said. “I used all the writer’s tricks. I did it as a third person chronological novel. I did it as a third person chronological novel with flashbacks. I did it as a first person novel. I just thought, if I could only find the right way to tell this story in this novel, then it would somehow unlock the whole thing. And I just couldn’t get it.”

She did complete a draft of the novel in 2003 but couldn’t sell it, so she shelved it. A year and a half later, she picked it up again—picked it up and tore apart the draft of her novel. She kept only 70 of the nearly 400 pages she’d originally written.

“It was amazing to start over with only those pieces that felt true. And then just to keep thinking about how to write it,” Joan said. She realized that the pieces she was keeping were not linear, but neither was her father’s suicide. And that realization unlocked the story for her.

“It was paralyzing for me to think in terms of a book,” she explained. “I decided to just do it in pieces and not worry about how the pieces were going to fit together for then. Just let it be the pieces.”

In reading both the memoir and Joan’s interview, I have learned so much about letting the story itself guide me, let it take the shape it wants to/needs to take and not the shape I think it should take.

You Know, Sex by Cory Silverburg and Fiona Smyth

This one is a book I purchased for Filha after reading a review of it somewhere in April. It’s billed as “the first thoroughly modern sex education book for every body, covering not only the big three of puberty—hormones, reproduction, and development—but also power, pleasure, and how to be a decent human being.”

It does not disappoint. Written and illustrated in vibrant graphic novel format, it is candid in the most thoughtful and thorough ways possible.

Cory, the author, is a sex educator who describes themself as “raised in the 1970s by a children’s librarian and a sex therapist, Cory grew up to be a sex educator, and author, and a queer person who smiles a lot when they talk.”

Fiona, the illustrator, said the goal was to make the book “accessible and visually engaging”—and her bright and empathetic work absolutely hits that target.

This is the kind of book that could have never existed back when I was hitting puberty—and if it did, my parents would never have let me read it because Jesus—but I wish it had. It’s brilliant and absolutely necessary. And Filha loves it. She’s read it cover-to-cover three times so far.

Come, Thief by Jane Hirshfield

Jane is a poet from Northern California who writes about small moments. The romance copy for this particular volume of poems goes on about her “full embrace of an existence that time cannot help but steal from our arms.” Maybe that’s why these poems resonated with me this year especially, as I watch time steal my mother inch by inch.

Here’s one of Jane’s poems called The Conversation:

A woman moves close:

there is something she wants to say.

The currents take you one direction, her another.

All night you are aware of her presence,

aware of the conversation that did not happen.

Inside it are mountains, birds, a wide river,

a few sparse-leaved trees.

On the river, a wooden boat putters.

On its deck, a spider washes its face.

Years from now, the boat will reach a port by the sea,

and the generations of spider descendants upon it

will look out, from their nearsighted, eightfold eyes,

at something unanswered.

Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire

I first read the words of Somali-British writer Warsan Shire back in 2015 when hundreds of thousands of refugees were fleeing Syria, Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and Eritrea only to be turned out, turned away, unwelcomed everywhere they knocked.

Warsan’s poem Home was circulated widely then, the blistering first line:

No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark clawing holes clear through the paper-thin reasons to refuse refugees. You have to understand that no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.

If you haven’t read the whole poem, you should go do it now, but here is the second part of the poem, a half that is no less powerful but often gets left behind:

Home II

I don’t know where I’m going. Where I came from is disappearing. I am unwelcome. My beauty is not beauty here. My body is burning with the shame of not belonging, my body is longing. I am the sin of memory and the absence of memory. I watch the news and my mouth becomes a sink full of blood. The lines, forms, people at the desks, calling cards, immigration officers, the looks on the street, the cold settling deep into my bones, the English classes at night, the distance I am from home. Alhamdulillah, all of this is better than the scent of a woman completely on fire, a truckload of men who look like my father—pulling out my teeth and nails. All these men between my legs, a gun, a promise, a lie, his name, his flag, his language, his manhood in my mouth.

Warsan’s first full-length poetry book includes Home and so many other aching poems that hit a 1-2 punch to the gut, then the heart.

Sister Tongue by Farnaz Fatemi

My friend and fellow writer/poet Melissa Fondakowski recommended this poet to me, and I never pass by a Melissa recommendation. Farnaz is an Iranian/American writer who is the current poet laureate of Santa Cruz county in California and founder of the Hive Poetry Collective. One reviewer calls this debut book of poems a “luscious love letter to language(s),” and I agree. Take, for example, this one:

The Only Mistranslation

is belonging. There is no word for it

in any of my tongues. There are

no tongues, so maybe that’s my trouble.

How to find a word inside a vacuum.

The din itself is home but home was never

a hearth, and that explains some things.

I belong deep inside my own gut, digesting

seeds rained from my ancestors’ dreams,

where compasses keep spinning, where

an avalanche of rare earth

blankets any inkling of sun.

I belong to my own hungry future

never oriented on the map

and never slaked.

A lover once looked down the well of my lungs

and called me nomad. I shook her off

but she was right about a magnet that keeps

moving in the night, stealing off to a different

north.

Stealing off to a new north

I confound myself, as if I were a butterfly

resisting pins.

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear by Mosab Abu Toha

I first became aware of this Palestinian poet on November 20 of this year when he was detained by the Israeli Defense Force as he had his family fled from the north of Gaza to the south along the supposed route of “safe passage.” He was holding his three-year-old son in his arms when the IDF pulled him from his family.

Mosab had just written two essays for The New Yorker about his life in Gaza under this most recent assault, The View from My Window in Gaza and The Agony of Waiting for a Ceasefire that Never Comes. In the wake of his arrest, The New Yorker raised the alarm, as did City Lights in San Francisco, who last year published Mosab’s poetry book. Mosab was beaten and interrogated by the IDF, then released a day after his arrest due to the public outcry from US literary organizations.

He was able to reunite with his family, and because his youngest son is an American citizen, born in the US while Mosab was studying at Harvard, the family was allowed to cross the border into Egypt. Mosab is now in Cairo, and on December 13 I attended an online webinar hosted by the Middle East Children’s Alliance in which Mosab recounted his harrowing experiences and mourned the loss of his dear friend and fellow poet Refaat Alareer who was targeted and killed by an IDF airstrike on December 7. Mosab also read us some poetry, including this one of his called Shrapnel Looking for Laughter:

The house has been bombed. Everyone dead:

The kids, the parents, the toys, the actors on TV,

characters in novels, personas in poetry collections,

the I, the he and the she. No pronouns left. Not even

for the kids when they learn parts of speech

next year. Shrapnel flies in the dark,

looks for the family’s peals of

laughter hiding behind piles of disfigured

walls and bleeding picture frames. The radio

no longer speaks. Its batteries have burnt,

the antenna is broken.

Even the broadcaster felt the pain when the radio

was hit. Even we, hearing the bomb

as it fell, threw ourselves

to the ground,

each of us counting the others around them.

We were safe, but our hearts

still ache.

BOOKS I CAN’T WAIT TO READ IN 2024…

Shit Cassandra Saw by Gwen E. Kirby

I saw this collection of short stories at Salted Books in Lisbon and thought the cover was rad. Then I read that it was a book in which, “virgins escape from being sacrificed, witches refuse to be burned, whores aren't ashamed, and every woman gets a chance to be a radioactive cockroach warrior who snaps back at catcallers” and I was like, SOLD!

The Woman They Could Not Silence by Kate Moore

We had an early Cousin Christmas at my sister’s house a couple of weeks ago, and she gifted me a hardcover copy of this title than I’m looking forward to digging into. It’s about Elizabeth Packard, a housewife and mother of six children who was locked away in an insane asylum by her husband in 1860. Instead of languishing in despair, Elizabeth launched herself wholeheartedly into a fight not just for her own freedom but for that of countless other women. She found she was one of many sane women on her ward who were committed to “keep them in line.” If you can call a woman “crazy” you can ignore her voice, right? Except Elizabeth refused to go quietly.

In Defense of Witches: Why Women Are Still on Trial by Mona Chollet

I’ve been thinking about the trope of witches as I write my own memoir, so this book caught my eye with the title alone. But then there’s this paragraph from the forward by Carmen Maria Machado that is just *mwah* chef’s kiss perfection and 70-decibel HELL YEAH: You’d be hard-pressed to find a more enduring and potent archetype than the witch; she has served as a shorthand for women’s power and potential—and, for some, the threat of those things—for much of human history. And yet, nowadays, witches have become a neo-liberal girlboss-style icon. That is to say, capitalism has gotten ahold of her; and, like so many things capitalism touches, she is in danger of dissociating from her radical roots. What could have once gotten a woman killed is now available for purchase at Urban Outfitters.

The Ogress and the Orphans by Kelly Barnhill

I already told you how much I love Kelly Barnhill but I don’t think you truly understand how much I LOVE KELLY BARNHILL. Somehow in my collections of Barnhill, I missed this one published in 2022. I’m so excited to have something new of hers to read—a tale about an ogress who isn’t who you think might she is: She had feet the size of tortoises, hands the size of heron’s wings, and a broad, broad brow that cracked and creased when she concentrated. Her skin was like granite, and her eyes looked like brand-new pennies. Her hair sprouted and waved from her head like prairie grass—stiff and yellow and green, sometimes spangled with daisies or dandelions or creeping ivy. Like all ogres, she spoke little and thought much. She was careful and considerate. Her heavy feet trod lightly on the ground…

This Here Flesh by Cole Arthur Riley

My sister-in-law Maria, an Episcopal priest, recommended this book and she has yet to steer me wrong when it comes to reading recommendations. Cole is well-known for her creation of Black Liturgies (which is also forthcoming as a book in 2024). The book descriptions of This Here Flesh call it a “work of contemplative storytelling” in which we are invited “to descend into our own stories, examine our capacity to rest, wonder, joy, rage, and repair, and find that our humanity is not an enemy to faith but evidence of it.”

Black AF History: The Un-Whitewashed Story of America by Michael Harriot

I don’t remember where I heard about this book—someone on Instagram, maybe Ibram X. Kendi or Ijeoma Oluo recommended it. I ordered it awhile ago and picked it up on my recent trip to the States. Written by columnist and commentator Michael Harriot, the book sounds like an important and necessary read, especially for those of us basking in the privilege of our whiteness. Here’s how the book is described: “America’s backstory is a whitewashed mythology implanted in our collective memory. It is the story of the pilgrims on the Mayflower building a new nation. It is George Washington’s cherry tree and Abraham Lincoln’s log cabin. It is the fantastic tale of slaves that spontaneously teleported themselves here with nothing but strong backs and negro spirituals. It is a sugarcoated legend based on an almost true story.

It should come as no surprise that the dominant narrative of American history is blighted with errors and oversights—after all, history books were written by white men with their perspectives at the forefront. It could even be said that the devaluation and erasure of the Black experience is as American as apple pie.

In Black AF History, Michael Harriot presents a more accurate version of American history. Combining unapologetically provocative storytelling with meticulous research based on primary sources as well as the work of pioneering Black historians, scholars, and journalists, Harriot removes the white sugarcoating from the American story, placing Black people squarely at the center. With incisive wit, Harriot speaks hilarious truth to oppressive power, subverting conventional historical narratives with little-known stories about the experiences of Black Americans. From the African Americans who arrived before 1619 to the unenslavable bandit who inspired America’s first police force, this long overdue corrective provides a revealing look into our past that is as urgent as it is necessary. For too long, we have refused to acknowledge that American history is white history. Not this one. This history is Black AF.”

Bodywork: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative by Melissa Febos

I’ve been a fan of Melissa’s writing since I first read her essay Wild Sublime Body a couple of years ago. She has a very confessional style and I’m greatly looking forward to reading her book about craft.

Salt Houses by Hala Alyan

The first novel from this Palestinian/American writer, poet, and clinical psychologist tracks the dispersal of four generations of a Palestinian family. Reviewers have called the book “lyrical and heartbreaking,” a work that “challenges and humanizes an age-old conflict we might think we understand—one that asks us to confront that most devastating of all truths: you can’t go home again.” It is certainly timely and I look forward to reading it.

Rifqa by Mohammed El-Kurd

If you can’t already tell, I have been seeking out the work of Palestinian writers and artists over the past couple of months. I recently purchased two prints from painter Sliman Mansour that are currently at the frame shop so I can hang them in my home. I’ve been reading, as well, and this book of poems is one whose arrival in my mailbox I eagerly anticipate. Hala Alyan, the writer just mentioned above, says of this poetry collection: “Rifqa is an absolute marvel, and El-Kurd is precisely the kind of poet—Palestinian or otherwise—we need right now: unafraid of the truth. The legacy of his grandmother, the eponymous Rifqa, flits across these poems, and with it comes wisdom, hope, and, most crucially of all, memory … El-Kurd doesn’t flinch from the violence and death that comes with dispossession. But make no mistake. These are the poems of the defiantly, unapologetically, wholly alive.”

Sharks in the Rivers by Ada Limón

In July of 2022, Ada Limón became the 24th poet laureate of the United States, taking the mantle from Joy Harjo (whose poetry I also highly recommend). Ada is Mexican/American and grew up in the Bay Area, and many of her poems carry the flavors of both of those histories. I have several of her poetry books but for some reason Sharks has been sitting on my shelf unread, so I plan to crack her open in 2024 and discover all the reasons why I should have read her sooner. Here is a sneak peek, the piece the book is named after, which is also the first poem you see upon opening the cover…

We’ll say unbelievable things

to each other in the early morning—

our blue coming up from our roots,

our water rising in our extraordinary limbs.

All night I dreamt of bonfires and burn piles

and ghosts of men, and spirits

behind those birds of flame.

I cannot tell anymore when a door opens or closes,

I can only hear the frame saying, Walk through.

It is a short walkway—

into another bedroom.

Consider the handle. Consider the key.

I say to a friend, how scared I am of sharks.

How I thought I saw them in the creek

across from my street.

I once watched for them, holding a bundle

of rattlesnake grass in my hand,

shaking like a weak-leaf girl.

She sends me an article from a recent National Geographic that says,

Sharks bite fewer people each year than

New Yorkers do, according to Health Department records.

Then she sends me on my way. Into the City of Sharks.

Through another doorway, I walk to the East River saying,

Sharks are people too.

Sharks are people too.

Sharks are people too.

I write all the things I need on the bottom

of my tennis shoes. I say, Let’s walk together.

The sun behind me is like a fire.

Tiny flames in the river’s ripples.

I say something to God, but he’s not a living thing,

so I say it to the river, I say,

I want to walk through this doorway

but without all those ghosts on the edge,

I want them to stay here.

I want them to go on without me.

I want them to burn in the water.

System Collapse by Martha Wells

And now for something a bit different! I’ve been reading Martha Wells for awhile—she writes excellent sci fi and fantasy, and I stumbled across her Murderbot Diaries novellas in 2017 or so. Set in a future of space travel and distant planets, the protagonist is a security droid—a SecUnit or, as the humans call it, a Murderbot. It’s a humanoid AI. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it: “The series is about a part robot, part human construct designed as a Security Unit (SecUnit). The SecUnit manages to override its governor module, thus enabling it to develop independence, which it primarily uses to watch soap operas. As it spends more time with a series of caring people (both humans and fellow artificial intelligences), it starts developing friendships and emotional connections, which it finds inconvenient.”

If that sounds weird, I promise it’s not! As one reviewer described it, “Murderbot's voice (is) a beautiful blend of exhausted cynicism and deep, helpless love.” System Collapse is the newest novel in this saga and I am so excited to read more Murderbot, I can hardly stand it.

A Psalm for the Wild Built by Becky Chambers

There’s more AI and space travel to be had! Well, maybe there’s space travel? Becky’s other books had it (the long way to a small angry planet is excellent), but since I haven’t yet read Psalm I can’t be sure. There is definitely AI, though. Here’s the logline: “Centuries before, robots of Panga gained self-awareness, laid down their tools, wandered, en masse into the wilderness, never to be seen again. They faded into myth and urban legend. Now the life of the tea monk who tells this story is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot cannot go back until the question of "what do people need?" is answered. But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. They will need to ask it a lot. Chambers' series asks: in a world where people have what they want, does having more matter?”

The Terrible by Yrsa Daley-Ward

Billed as “a storyteller’s memoir,” I bought this book three years ago before we moved to Portugal with every intention of reading it immediately. I have not yet read it. But as I pulled it from my shelf to write this description, I felt again the urgent pull to sit down and read it right now. Here’s why: “This is the story of Yrsa Daley-Ward and all the things that happened. Even the terrible things. And God, there were terrible things. It’s about her childhood in the northwest of England with her beautiful, careworn mother Marcia; the man formerly known as Dad (half fun, half frightening); and her little brother Roo, who sees things written in the stars.

It’s also about the surreal magic of adolescence, about growing up and discovering the power and fear of sexuality, about pitch-gray days of pills and powder and connection. It’s about damage and pain, but also joy. With raw intensity and shocking honesty, The Terrible is a collection of poems that tells the story of what it means to lose yourself and find your voice.”

Losing ourselves and finding our voices… an extremely necessary undertaking for each one of us again and again and again as we go on through our lives.

Thanks for reading such a scroller of a post about reading! Now let’s all go curl up with a blanket and read some more, yeah?

Permanent Postscript: If you enjoy my writing and you’d like to support it/me in some small way, you can leave a tip on my Tipeee page. No obligation or expectation. Whether you’re a longtime reader or a first-time visitor, I’m grateful to you for reading, for commenting, for sharing, for subscribing, and for sending good vibes. Thank you!

Copyright © 2023 LaDonna Witmer

LaDonna, you are killing me! My bookshelves are already groaning after my day (WHOLE day) at Powell's. But thank you too, this is so exciting. Read "Lioness" as per your last Scrawl and loved it. I've waited almost 10 years for "Menewood," so that's my Christmas. After that! Hope you're doing well!

Great list LaDonna and so glad you got to read Farnaz’s book! We were in Mills together and this is her first!