I don’t think of myself as a Person Who Leaves. Even though I have left, time and again.

I was born on the eastern coast of the United States near the Chesapeake Bay, but I left before I could speak. My parents moved us to Illinois, the state where they both grew up, when I was two. I spent my childhood in a big grey farmhouse just west of Ronald Reagan’s hometown of Dixon. It is the only childhood home I remember, but I left it behind as well. First I moved 42.7 miles east to attend a university. Then I moved to a neighboring state for a post-graduate fellowship at a big-city newspaper. Then I settled 75-ish miles away in various tiny apartments in various Chicago suburbs while I broke myself in as a writer (first as a newspaper reporter, then as an advertising copywriter). It only took me a handful of years to realize that 75 miles wasn’t far enough away from the hometown I had come to loathe, so I packed up my books and pens and brand new husband and drove a U-Haul west for three days until I reached the Pacific Ocean. In San Francisco I finally found a place where I believed I belonged, and I put down roots and set up house and told everyone I was never leaving. Until I left 20 years later and moved to Portugal, putting an entirely different ocean between me and the land of my birth.

So I guess I am a person who leaves.

But am I a person who runs away?

That’s what my friend Ryan asked me recently, although not exactly like that. What he actually said was, “I have a question I think you should write about: What are we all running from, those of us who have moved away from our homes?”

“Or are we running at all?” I countered.

“Yes,” he said, “exactly. I think you should write about it.”

I can’t speak for Canadians or South Africans or Brits, but there’s plenty for Americans to run from, and the list only grows longer as the years tick on. The endless surge of mass shootings, the utter lack of reasonable gun control or reasonable healthcare or reasonable college tuition, the overbearing need to control women’s bodies, from what they wear to what they do with their wombs, the unscalable chasm between rich and poor, the overfunded war machine, the underfunded schools, the systemic racism, the pervasive sexism, the chronic homophobia and unapologetically vicious prejudice against transgender folk, the religious hysteria, the addiction to capitalism, the empty cult of celebrity, the unhinged conspiracy theories, the ruthless theocrats, the inbred jingoism, the fanatical belief in American exceptionalism, the ridiculous performance of patriotism, the political system that’s designed to fail the people it claims to represent, the leaders commandeered by corporations, by greed, by delusions of grandeur: old white men clutching their pearls of power. *deep breath* I could go on.

I am sometimes jealous of those who feel a deep connection to the land of their birth, to the loam and the water, the particular flavor of the air in that place. I stand in awe of indigenous people who know exactly where they came from, can trace the claim of generations, all the bloodlines leading back to the very same place as if they sprang whole and hearty from the soil itself.

I don’t feel that connection to the United States of America. I don’t have an ancestral home. My people are a hodgepodge of whiteness. Settlers from somewhere else who planted themselves here and there. The most recent generations hail from Illinois and Indiana. But even there, they were always moving. Never fixed. The family farms belonged to the family only for a generation before being sold to the next available opportunist. All that acreage changing hands because the need for cash was more pressing than heritage. There are no threads that connect me to the land where I was born, nothing but memories lingering between me and the green-shingled farmhouse where I spent my childhood.

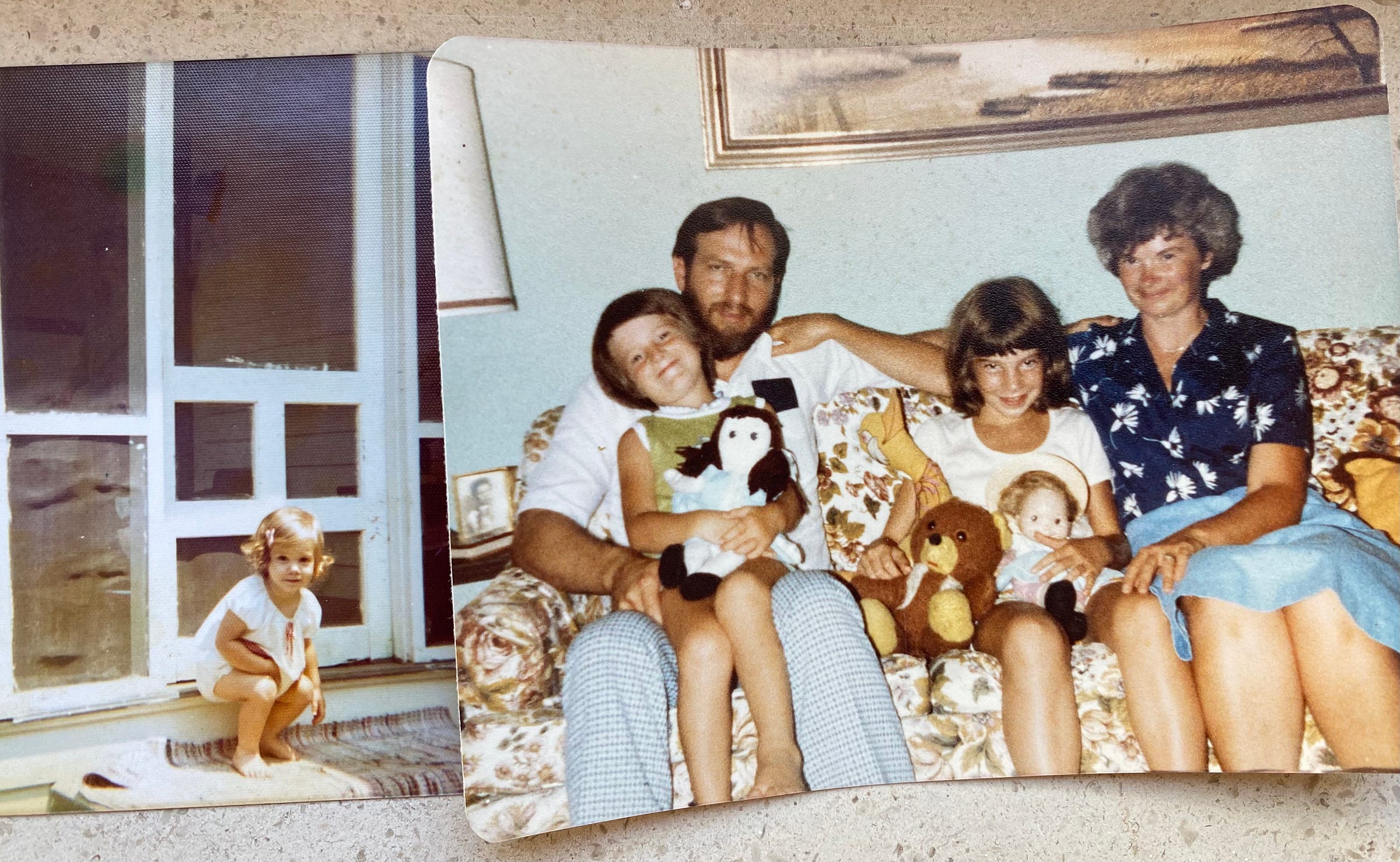

When I was 11 my family took an uncharacteristic vacation, borrowing my Great-Uncle Merle’s truck-top camper for a five-state drive from Illinois to Virginia. My parents wanted to show my sister and I where their story started: Buckroe Beach where my dad proposed; Newport News where they brought me home from the hospital and placed me in a green crib painted with woodland creatures from Bambi.

My dad was twitchy with excitement as he navigated the old neighborhood, telling us about the tree they planted in the backyard, wondering how big it might be now, nine years on. His excitement turned to consternation as he drove up the street where we once lived and discovered that our home was gone. In its place was asphalt and cars: a McDonald’s parking lot.

It’s not just that I can’t point to a physical building and say, “That is where I came from.” It’s that I don’t even know where my people’s people came from. There are no stories passed down from elderly hands to young hearts. No “back in the old country” tales. I don’t know what the old country was. What the old countries were, because doubtless my people come from more than one place.

On a rail trip through Europe long before Filha joined us, Marido and I crowded into a phone booth in Switzerland and looked up the Ws. We found an entire page of people who shared his last name, and a handful who shared mine. Maybe in some long-lost universe a relative of his and an ancestor of mine shared a fencerow.

I don’t know. I’ll never know.

Does that lack of information make it easier for me to move about the planet? I’m not tethered in place by a story of belonging. When the going gets rough, I can just pick up my things and go.

Is that why I left the States? Because the going got rough? For a middle-class, dual-income family of white people? (I mean, boo-fuckity-hoo, right?)

No, it wasn’t all that rough—aside from the long list of Things Wrong with America above. It wasn’t that rough for Marido and I, but Filha had only just begun her story and already she had nightmares about being gunned down at her elementary school.

If I say we left for her, if I say we left to give her a bigger chance at a better life, that would be the truth.

But we left for ourselves, too. Because why live the length of your days in the place where you were born simply because that’s the place where you were born? Why hang on to a dream you no longer cherish, why remain in a country you don’t believe in? Why stay in a land that never really belonged to you?

Every time I left, I left not because I was running away but because I was running toward. Because I wanted a hope and a future, and I couldn’t find either in the places I left behind.

I left my hometown for a place that would give me an education. I left the Midwest for a place that granted me ease of being. I left America for a place that returned to me the ability to breathe deep and let down my guard.

I could have stayed. In all those places, I could have stayed and built a life and feathered a nest and become an entirely different version of myself. I could have laid claim to a piece of land like (I imagine) my forebears did before me. I could have raised up a fourth generation of Witmer in the rich black earth of the Sauk Valley.

Maybe that would have been a perfectly decent story. Maybe it would have had a happy ending. Maybe staying would have killed me.

In this version of the telling, I found the courage to leave.

Sometimes it’s right to stay and fight for what you believe in. Sometimes it’s right to recognize that the fight isn’t winnable, that the American Dream doesn’t exist, that you bought yourself a truckload of patriarchy and propaganda. And if that’s the case, you leave. (As they say, “If you don’t like ‘Murica, get out!”)

Of course I recognize the absolutely colossal privilege of being able to leave. I had both the means and the motivation—some folks have neither. Leaving is a desperate dream that will never be in reach. Staying is a fervent wish that will never come true. I was lucky—not that I made good choices but that good choices were available to me.

I’m doing my utmost to make the most of them.

If you want to support my work…

You can choose from a couple of tiers of paid subscriptions. In addition to my undying gratitude for your support, you’ll get more of my writing, which is what (I assume) you’re here for! Once a month for paid subscribers only, I will post an excerpt from my memoir-in-progress. The first one is here, for free, if you want a preview.

OR

If you’re not into paid subscriptions, but you’d still like to show support every once in a while, you can leave me a tip.

OR

If you want to carry on reading these posts for free because you can’t or shan’t pay, that’s perfectly fine. I do not hide Long Scrawl essays behind a paywall.

NO MATTER WHAT

Thank you for reading. Thank you for telling me when my writing means something to you. That matters most of all.

Copyright © 2024 LaDonna Witmer

This post felt so personal for you but as well as for me and many others. I grew up as a military kid traveling every two years to somewhere new, sometimes in the US, sometimes in lands foreign. When my father retired in Texas, I never felt at home there, and as time passed and I grew older, I realized I was lucky enough to go somewhere else. And it sure as hell wasnt going to be in the USA during this crazy period. We won’t be staying forever in Portugal as much as we love it—taxes will kill us. But we’ve already started thinking of our next stop. Will it be back to the USA to somewhere reasonably sane like another writer mentioned (Santa Fe) or maybe we will find ourselves lucky enough to obtain an EU passport and go where there are still no guns and reasonable people? Who knows, but I think we are always evolving and changing and for right now, we are so happy we made the decision to leave the USA and come to this beautiful land and get to know the wonderful people and culture. Thank you for generously sharing your talent of expression with us.

Thanks for sharing your thought processes LaDonna. As someone who also has a school-aged child and left the U.S. for a different, and hopefully better, life in Portugal, I can relate to much of it. I have moved quite bit in my life and have never really thought of it as running from something so much as a just one chapter ending and it being time to start the next. I moved every few years as a child and at the time I was envious of people who had roots and lifelong childhood homes. But now as an adult I have replicated the same patterns as it feels totally normal and natural to me. Though I do hope we stay put for a while now.