School has been the hardest thing.

Hands-down, no question, figuring out school for Filha has been much more difficult than establishing residency or changing our address with various Portuguese bureaucracies or buying a house or finding new friends or even learning the language.

It wasn’t always hard. Back in the States, her preschool was a dream. It was just three blocks from our house, an easy walk down the hill toward Ocean Beach. The teachers were amazing, and the school was a safe place not just for our tiny toddler, but for Marido and I as fresh and frazzled parents. Filha met her best friend there, at age 2, a girl who loved bugs and slugs just as much as (maybe more than?) Filha herself. When it was time to head off to kindergarten, we got lucky again. The SF public school lottery landed us not only at a really great elementary school, but once again in the company of her bestie. On the first day of school, there they stood hand-in-hand, giggling away in line with their new classmates and their new teacher like no big deal.

Filha loved that school. It was an unassuming rectangle perched on the banks of a lake that housed ducks and grebes and coots and rowing club shells shooting across the early morning water. Occasionally a loose cannon coyote would wander up near the parking lot and cause some excitement.

We kept getting lucky with teachers. Every year, in each new classroom, Filha would be welcomed by a kind, smiling face who would shepherd her curiosity undiminished through another grade. Every year, her new teacher would be her favorite teacher.

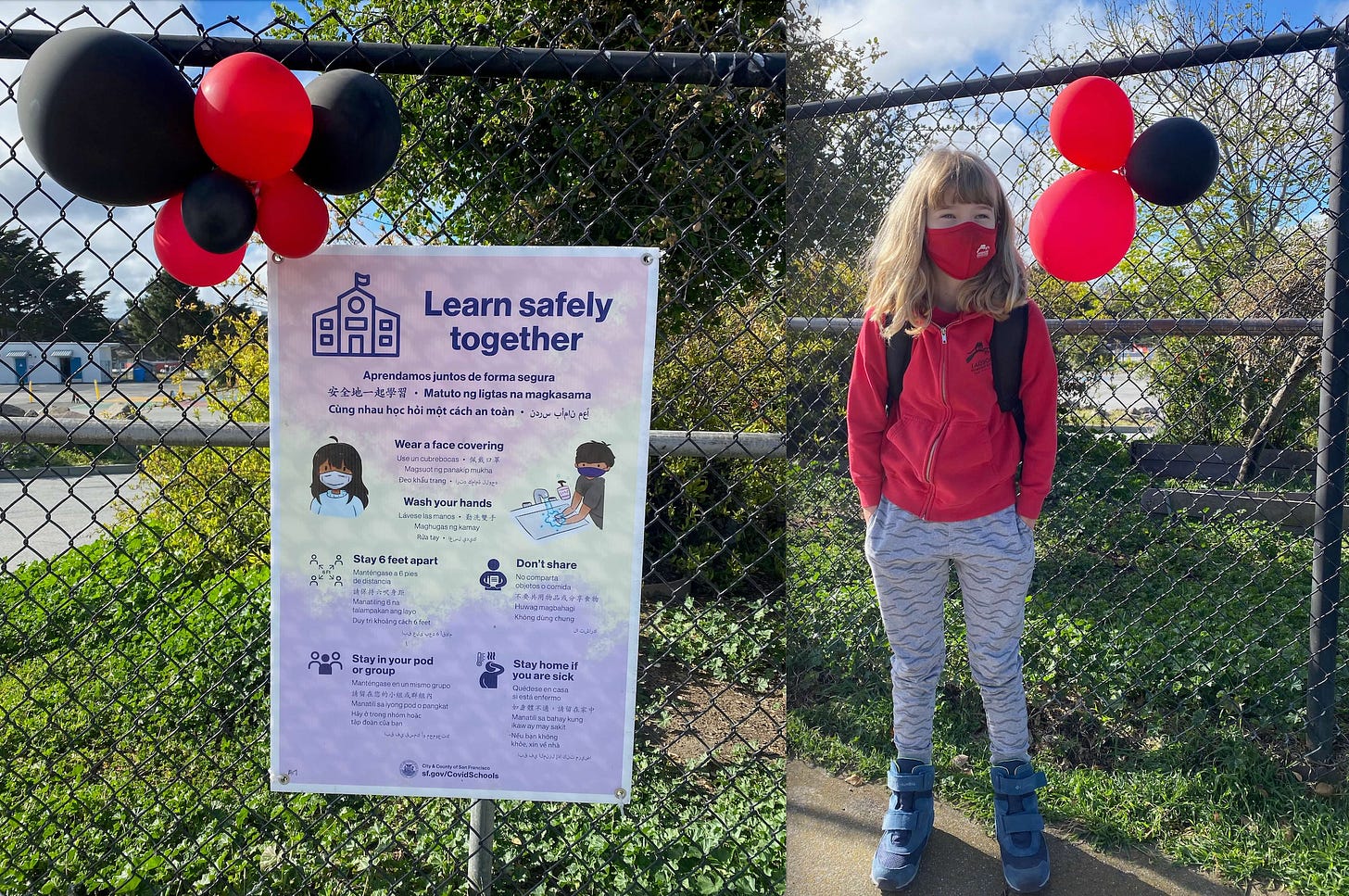

COVID came in third grade, and none of us knew that particular March day would be the last normal day of school at Lakeshore ever. We all struggled through those spring months, hopeful that summer would burn off the virus and 4th grade would meet in person. But of course that didn’t happen. From August of 2020 to April of 2021, Filha’s classroom was a collection of pixels. Her teacher was outstanding, as usual, but nothing can replace face-to-face connection.

Somewhere in those months, we decided we were moving to Portugal. So when the announcement came that the school would return to in-person classes on a hybrid schedule, half the class on campus for half the week and the other half online, it was bittersweet. Filha soaked up every on-location second of those final weeks, but it still wasn’t enough. When the bell rang on the final day of school, she was distraught. “I don’t want it to be over,” she sobbed.

I think it will be years before we as a society reckon with the true toll the pandemic took on kids. At a very practical level, 4th grade is when you learn basic fundamentals of multiplication and division—building blocks you’ll rely on for the rest of your mathematics career. It’s pretty difficult to cement those blocks in place in a 30-minute zoom class.

Academically, in many ways, Filha is still catching up. I imagine that’s true for most of her peers.

Marido and I did not uproot Fila from her beloved school without a great deal of thought and care. She had one year left at Lakeshore. If we had stayed in the United States until 2022 instead of leaving in 2021, she could have graduated from 5th grade with her friends.

But the urgency of leaving when we did felt imperative, for a host of reasons. So we measured the risks and counted them worth the cost.

Of course we researched schools in Portugal, specifically in the Setúbal area. We knew that we didn’t know everything but we thought we had done our due diligence and felt cautiously optimistic.

“Kids are so resilient,” everyone told us. “Kids adjust so quickly,” they said. “Kids pick up languages so fast! Give her 6 months and she’ll have a pack of new friends and be speaking Portuguese like a native,” they said.

I know better than to take to heart all the They-Said-Platitudes you get handed by every Tom, Dick, and Harry. I kept my previously mentioned optimism turned down to a dull roar.

But still. I was optimistic. Maybe it would work like magic, I thought. Maybe she would make new friends just like that. Maybe she would learn the language in a flash. Maybe school in a new country would be just as easy as school in the old country.

“Hah,” is what I have to say to all that now. Hah.

It’s kind of sweet, really, all the naive things you imagine just before you step off the cliff.

The thing about moving to a new country is that you don’t know what you don’t know. This means you don’t ask the right questions, because the right questions haven’t even occurred to you. You don’t have the language to ask—literally or culturally.

So yes, we talked to school administrators on screens before we moved and we toured schools in person before we had even slept off the jet lag. We googled and we emailed and we debated and we took all the information we could gather and made the best decision we could.

And you know what? It didn’t work out. Not at all.

Attempt #1: Private School

The first school we enrolled in was a small private school in Setúbal, preschool through 12th grade. They had a small farm. They had a family of school goats: Almond, Peanut, and their daughter Cashew (Amêndoa, Amendoim, e Caju). There were only 10 kids in Filha’s 5th grade class. The head 5th grade teacher was a lovely young woman who spoke excellent English and took Filha under her wing immediately.

It seemed idyllic. The goats would just wander into school, right in the middle of math class! We thought a small school would ease our (super shy, intensely creative) daughter’s entry into this new world. Sure, she hated the school uniform, but it was just a polo shirt with the school’s crest sewn on a patch, and navy blue pants. Not too bad, we thought. And yeah, the school days were long: 8:30am to 5pm. But maybe the extreme immersion would help her learn Portuguese even faster, we thought. And, you know, there were goats!

On the first day of school in the middle of September, 2021 I dropped Filha off at the school and locked all my worries and reservations away down deep inside my body. It was gonna be fine. She was gonna be fine. Everything was fine!

“I miss Lakeshore,” she whispered quietly as we sat in the parked car outside the school. “I miss my friends.” A tear rolled down her cheek, then another.

“I know, baby, I know,” I wiped the tears with my thumb. “We’ll just take it one day at a time, ok?”

She nodded and she swallowed those tears way down deep inside her small body.

She shouldered her backpack and shoved her fists into her pockets and walked through the sliding glass door, alone.

I got back in the car and took deep, gasping breaths.

“It’s gonna be fine!” I told myself, fiercely.

And it was fine. Sort of. There was only one girl in Filha’s class who spoke English. She was loud and funny and made it her mission to draw my daughter out.

What most extroverted people don’t understand is that it takes awhile. Some of us introverts can fake it better than others. Some of us have an arsenal of skills we use to pull ourselves out of our tightly coiled shells. But Filha was only 10. She was just beginning to assemble her arsenal. Every class she’d ever been in, she started slowly. At the beginning of the year her teachers would tell us, “She doesn’t talk much. She keeps to herself.” But by the end of the year, they’d report that she was talking all over the place and firmly ensconced in the ecosystem of the classroom.

It takes awhile. And it turned out, she didn’t have that much time.

One Monday evening 5 weeks into the term, I received an email from the school administrator. It was sent to all the parents: “Our school is closing down,” it read. “Suspensão de funcionamento.”

“We deeply regret the inconvenience caused to students and families. We did everything to avoid, but it was not possible in a timely manner. You have two weeks to find a new school.”

We had visitors that week, our first since we had arrived in Portugal. We were just getting ready to leave the house to go out to dinner. I couldn’t go. I couldn’t focus.

“How in the world does this happen? What does this mean? How can they just… CLOSE? What the actual fuck?!” I said to Marido. He was as flabbergasted as I, but he can fake it better. So he went out to dinner with our friends. I stayed home and googled, frantically.

Attempt #2: A Different Private School

The thing is, we had been interviewing with private schools in Setúbal all spring. There aren’t that many of them, and the seats fill quickly. I wasted no time in reaching back out to the other two schools that topped our list of possibilities. It was no use. It was the middle of the fall term, and all the private schools were full.

I tried to figure out which public school we were zoned for and then took myself to the campus early one morning as students were filing in. I went to the school office but couldn’t find one single person who could speak English. At the time, my own Portuguese skills were limited to a few paltry phrases. I could barely make myself understood.

At one point I just panicked and burst into tears.

“Calma, calma!” the secretary told me, and led me to a chair. “Pode esperar aqui,” she said and bustled away. She returned a few minutes later with a student, a French girl who spoke some English.

Together we muddled through, I told her what had happened and asked about the possibility of Filha attending that school. They looked up my address. Turns out I was at the wrong school.

It wouldn’t have worked, anyway. Not then. Filha was glad to be in Portugal, she loved it. But she was missing her school and her friends and she was overwhelmed by the learning curve of language and systems and people that were all completely foreign.

She needed a small, safe environment. We thought we had found it with the goat school. But now that was gone and I was desperate.

During this time, several people pushed us toward a large, private international school just up the hill from Setúbal. I had known about the school well before we moved, but had crossed it off the list of options. Now that list of options was decimated, so Marido and I went to tour the school.

I didn’t have to set foot on the grounds before I knew it was a no. There were so many things that raised a warning: The uptight school uniforms with knotted ties and plaid pleated skirts. The multitude of fast shiny cars dropping off kids and whirling away. The way the school rep told us, smugly, that all school supplies—even notebooks and pencils—must be purchased from the school itself because they bore the school logo. (Can’t have any of those pesky individualistic pencils!) Then there was the way parents talked about the school as if having a child enrolled there was a status symbol—a famous footballer’s children attend there, you know.

It was all that and so much more but most of all it was the simple fact that I know my child. And I knew this school would crush her.

So we crossed it off the list. Again.

We ended up at a nondescript private school just outside Pinhal Novo. I’d never heard of the school, it had never come up in all my searches. But a friend of an acquaintance sent her boys there, and they reportedly liked it.

And there was one seat left in the fifth grade classroom.

We toured the school. It wasn’t anything special, but it wasn’t anything awful either. The administrator who gave us the tour was friendly and promised that Filha would be well taken care of. There was no program at the school for lingua não materna, but that wasn’t going to be a problem, the school assured us. They would help Filha with Portuguese. She would be supported.

Filha wasn’t excited about the school. But two of the kids from her now-defunct previous school were there, and although they weren’t exactly friends, they were familiar. Also, we were out of options.

We signed her up.

It lasted four months, from November through February, and each day was worse than the last. By the end, Filha was crying every morning on the way to school.

The days were long once again, from 8:30 to 5:30—I’ve since discovered this is a private school perk. Parents pay tuition so they can deposit their kids in one place all day while they’re away at work. (Personally, I don’t believe an adult can stay focused for a 9-hour day, let alone a child. So super-long school days are not a perk to me.)

All the school’s promises of support for Filha turned out to be bullshit. I have multiple theories about why, but the crux seemed to be that the private school was a for-profit business endeavor. The people who ran it cared more about money and status than about quality of education, or the importance of having even a basic understanding of child development.

Most of Filha’s teachers did not speak English at all, and made no attempt to include her in their lessons or try to help her in any way. The prevailing attitude seemed to be that if her body was in the room, she would just pick up Portuguese through her pores, by osmosis.

She started taking books to school, long chapter books that she’d read throughout the day since she was otherwise being ignored. By the end she was finishing three 200-page books a day.

There were some really sweet kids in her class, including two girls who took her under their wings and did their best to make her feel at home. And there was the kindergarten teacher who had lived in the UK for a few years and spoke excellent English. Whenever one of Filha’s teachers wanted to communicate with her, they’d interrupt the kindergarten teacher in whatever she was doing with her own class and ask her to come and talk to Filha for them.

During our fraught tenure at the school, I asked multiple times if I could talk to Filha’s teachers and try to work out a plan to make things better. The head of the school refused. I was not allowed to meet the teachers or talk to them. Ms. L, the kindergarten teacher, told me that this was the school’s policy—none of the teachers were allowed to talk directly to the parents. It was bizarre.

In a last-ditch effort, I finally met with the head of the school, with Ms. L translating for us. There was a lot of insincere smiling, a lot of long meandering sentences about how it wasn’t the school’s fault that Filha wasn’t adjusting at all. There was a great deal of concern that I kept sending snacks in my child’s backpack because she didn’t eat the school’s prepared lunches (according to Filha, it was a lot of “really cold spaghetti”). I left the meeting knowing it wasn’t going to work out, and feeling completely defeated.

How could I keep sending my child into misery five days a week when there was absolutely no silver lining? She wasn’t learning anything. Nothing. We were 3/4 of the way through her 5th grade year and it was a total bust. Something had to change.

Attempt #3: A Private Tutor

One day I was waiting at the school to pick up Filha (parents had to wait outside the school in a queue and one by one, you’d get to the front and tell the person at the door your child’s name, and they’d disappear and maybe 15 or 20 minutes later they’d come back escorting your child as if they were a toddler who might get lost on their way from the classroom to the front door.) So I was waiting for Filha to appear, and Ms. L the kindergarten teacher was out in the front playground with her class. We were casually chatting (keeping it a bit clandestine, since we weren’t supposed to talk!) and I said, “You know, I’d rather pay you the money I give to this school each month and have you just come to my house and teach Filha all the subjects!”

“Like a private tutor?” Ms. L said.

“Exactly,” I replied.

Two days later she called me. “If you were serious about that offer, I’ll do it,” she said, “I’ll quit my job. I hate working at that school anyway.”

And that’s how, in March of 2022, we ended up hiring our own private tutor. Like some sort of hoity-toity fancy family.

It started off pretty well, with Filha and Ms. L animatedly discussing World War II and the earthquake of 1755 and the Salazar dictatorship, curled up in front of the crackling fireplace, cups of hot chocolate/coffee clutched in their hands.

It started off well, but it ended badly. And it was in no small way my fault.

I return again to the truth that when you don’t know what you don’t know, you don’t ask the right questions. And I did not ask the right questions of Ms. L.

I was also quite desperate, so I brushed aside several red flags at the outset and made uncomfortable peace with the fact that Ms. L seemed to have no appreciation of modern child psychology. As time went on, she leaned more and more into old-school methods of shame and guilt to get Filha to do what she wanted. Techniques that were familiar to me from my own years in a strict religious school, and that I have no doubt Ms. L had experienced personally as a child herself.

There were also major cultural differences, in expectations and in understanding. Just because Ms. L was fluent in English, just because she had lived in the UK, did not mean that we truly understood each other. Even when we said the same words, even when we came to an agreement. Our individual understandings of those words and agreements were vastly different.

At first glance, Ms. L was the type of person who seems very confident. She had loud opinions and a boisterous personality, and she was delighted with Filha. In the beginning, all of those characteristics combined to pull Filha from her shell a bit, to make her feel seen and safe.

But as time went on, Ms. L’s enthusiasm for teaching Filha faded away. Her attention wandered. She’d make bold pronouncements about field trips and hands-on learning and real-world skills and in-depth Portuguese lessons, but then fail to follow up on any of it. And I failed, too.

I failed to have honest confrontations in which I brought up the red flags and the empty promises. I pulled my punches. I second-guessed my intuition. I was determined to make this work because so much else had failed. I was desperate for Filha to recapture her curiosity, her love of learning that the previous two school experiences had tamped down.

And I genuinely liked Ms. L as a human being. I liked her a lot. She was funny. She was interesting. We had great conversations about all kinds of things. We shared a fucked-up religious upbringing, one that she was only beginning to deconstruct and heal from. I felt big sisterly toward her. I loved her kids and her dogs. Our families hung out. They invited us over for birthdays and Christmas Eve. I didn’t want to have hard conversations with her, I just wanted to be friends. I just wanted it all to work out.

Ms. L and Filha finished 5th grade, took the summer off, and then we all agreed to go with private tutoring again for the 6th grade school year. As part of our arrangement, we had signed up as homeschoolers with the local public school district. (We had by this time moved to Palmela, so it was a different public school than the one I had tried to enroll Filha in back in 2021.)

Our ultimate goal was to ready Filha to re-enter the school system. It was never our intention to keep her isolated with solo tutoring forever. But in the fall of 2022, she wasn’t ready yet to take that leap. So we pushed forward with Ms. L’s tutoring, even though the cracks widened exponentially as the months marched on.

In the early weeks of 2023, it all fell apart. Marido was away for work for five straight weeks, and a number of things happened during his absence that made it absolutely clear the tutoring plan was unsustainable.

At the end of January, I sat down with Ms. L for what I thought would be a really hard conversation. I rehearsed what I wanted to say on my way to the café. I called my sister for moral support. Once there, I wiped my clammy hands on my coat and forced myself to get to the point: “Its pretty clear that you don’t want to do this anymore,” I said. “This tutoring thing isn’t working for any of us.”

To my surprise, she didn’t object. She agreed, strongly. She didn’t seem surprised, or bothered. We parted ways amicably. Or I thought we did. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that everything went sour and we both stopped texting, calling, speaking.

I don’t feel good about the way it all ended. To this day, it’s a tight knot in my head that I roll around, examine from all angles, try to figure out how to untangle it without the magic of time travel allowing me to just go back and do it over, do it differently.

Ultimately I did what I did to protect my kid. I could have done it better. I could have done it sooner. I could have curbed my desperation and tried harder to find a different solution.

But I didn’t know the right questions to ask. I have only learned the right questions by asking the wrong ones.

The StopGap: Tutoring Center + Dad School

Once we ended the relationship with Ms. L, I went to the public school for help. Perhaps we could enroll Filha in the middle of the term, I thought. I didn’t know what to do.

The best thing about the tutoring/homeschooling chapter was the connection to the public school. A teacher there reviewed Filha’s portfolio of work at the end of every term. This meant that the school administrators and several teachers were already familiar with Filha. So they were excellent partners as I tried to figure out what to do in the aftermath of Ms. L.

It was the director of the school who suggested a stopgap measure: a tutoring center. These exist all over Portugal, multiple tutoring centers even in the smallest of towns. I had seen them, but didn’t know what they were, exactly. I didn’t know that I should ask.

Tutoring centers here are similar to those in the States in that they have adults who help kids with homework. But in Portugal, they are more than that. Many public schools here operate in shifts. There is the morning cohort of students and the afternoon cohort, and each of them spend about five hours a day in school, at class (as opposed to the 9 or 10 hours a day at private schools).

The problem is, parents are at work all day and they need a place for their kids to go in the intervening hours. Many of them use the tutoring centers. Before or after school, kids go to these centers to actively learn with a tutor at their side or to quietly work on homework, read a book, have a snack.

The director thought a tutoring center would be a perfect way for Filha to get support in learning Portuguese while also being around other kids her own age.

We found one situated midway between the school and our house, and in April Filha began attending Portuguese lessons there three times a week. The rest of the schooldays she spent in “Dad School” as Marido did his best to pick up the slack and teach her math and science. They took long bike rides for PE class. She learned how to make menus and go grocery shopping. It wasn’t perfect, but it was the best we could do.

Filha herself turned a corner during those months. “I’m ready to go back to school,” she told me one day. “I miss being a part of a big class. I know it will be hard and I know I don’t really speak Portuguese yet, but I want to go to the public school.”

Attempt #4: Public School

Luckily, we had planned ahead. Filha had already been attending a weekly art class at the public school for 6 months. It was my idea, because I knew that if we could ease her into the school, let her wade slowly into the shallows instead of dunking her in the deep end all at once, she would find her own way. Then that first day of full-time school wouldn’t be so intimidating.

And that’s what happened. The art class had familiarized her with the school grounds. The art teacher and all the kids in the class had been extremely kind and welcoming, and she had enjoyed the experience. So when the first day of school rolled around this September, Filha was nervous but she wasn’t terrified. When I picked her up at the end of the day, she was smiling and full of stories. “I would say it was a positive first day,” she reported.

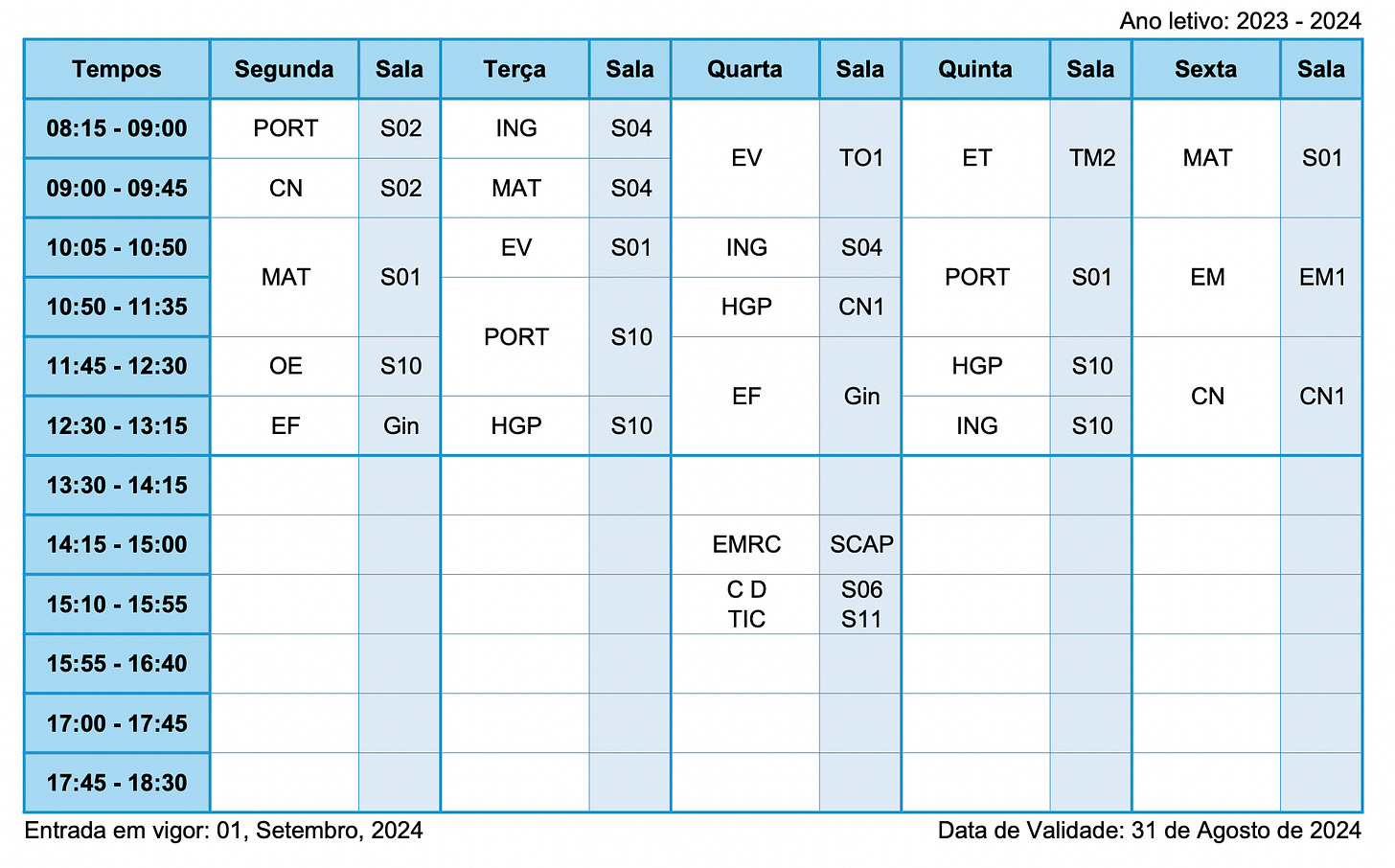

This week will be her 9th at the public school, and she’s thriving. I can’t say that she loves it the way she loved Lakeshore. But she knows her schedule by heart and has mastered moving from class to class. She knows when to run to her locker for supplies and when she can perch in a tree and read a book for awhile, or hide out in the library with her pal Iris and draw dragons (Filha) and anime (Iris) for an hour. She never fails to come home with stories about what this kid did or that teacher said. Later today, she’s attending a birthday party for one of the girls in her class.

Although she’s got one big bummer of a teacher who yells and throws notebooks on the floor to get kids’ attention, the rest of her teachers have been extremely supportive. They find creative ways to help her keep up with the class even though her Portuguese isn’t quite up to snuff. Within the first three days of school, she already had a favorite teacher with whom she felt safe enough to talk about her trouble with a boy. Now she has two other teachers who’ve joined her list of favorites, and she tells me stories all the time about how they go out of their way to show her small kindnesses and encourage her.

She’s still attending the tutoring center three afternoons a week after school. Sometimes she gets help with homework. Sometimes they just focus on Portuguese.

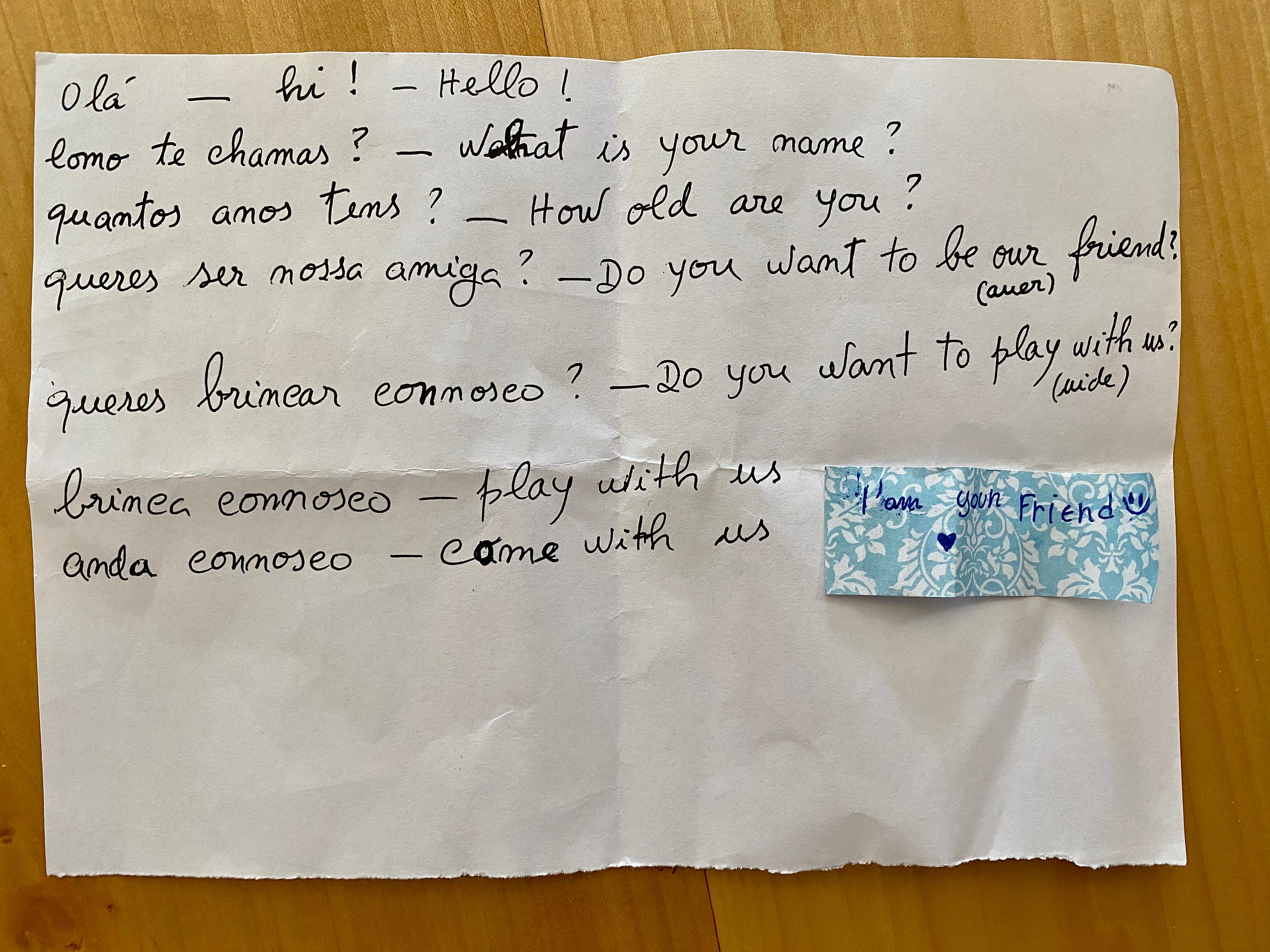

If you ask Filha how her Portuguese is coming along, she’ll duck her head and say it’s not very good. But she’s been correcting me on my pronunciation for awhile now. And often at school, the pack of girls who’ve adopted her as their very own American friend will say, “It’s your turn now!” Because they’ve been practicing their English on her, and now they want to hear some Portuguese.

One Wednesday I picked Filha up and she was laughing as she waved goodbye to a gaggle of girls at the gate. “Today they asked me to say the names of some animals in Portuguese,” she told me. “I think they expected me to say just gato or cão, but I was like Macaco! Papagaio! And they all clapped and cheered for me. It was hilarious.”

People ask me quite often about our experience with school in Portugal, and I see posts on the expat groups all the time from parents who want to move abroad but have all kinds of questions about how their children will fare. And there is never a shortage of replies to those posts from people who are absolutely sure that those kids will be fine! They’ll adjust! They’re so resilient! They’ll make friends so quickly! They’ll speak the language like a native in no time at all!

And maybe this is true, for some kids. But for others, it’s horseshit.

Because it depends. It depends on the child. It depends on the school. It depends on the teacher. It depends on age and personality and previous experience and parents and families and location and so many things! It just depends.

We have friends whose kids have attended the big international school that we rejected. Their kids loved it. Their kids are thriving. Their kids are their kids.

I know what is true for my own child, and this journey that our family has been on is absolutely unique to us. The challenges, the mistakes, the questions we didn’t ask—those are all relative to our own experience.

Still, I’ve been writing this post in my head for months. Because if I were on the other side, if I were hoping to relocate to a new country with my kid, I would want to read this kind of story. Even if the personal details are different, I think it’s helpful to hear about other people’s experiences, and maybe even use some of that information to inform one’s own decisions.

It’s been such a long journey, and I know it’s not over yet. But Filha is on her way, and that’s the entire point.

Permanent Postscript: If you enjoy my writing and you’d like to support it/me in some small way, you can leave a tip here, on my Tipeee tipping page. No obligation or expectation. Whether you’re a longtime reader or a first-time visitor, I’m grateful to you for reading, for commenting, for sharing, for subscribing, and for sending good vibes. Thank you!

Copyright © 2023 LaDonna Witmer

Wow! I suspect that you've been writing this post in your head for far more than a few months.... Thank you for sharing, we who've been here for a while know that it's not easy, whether to learn the language or to voice doubts, it's all supposed to be wonderful... but it's life, after all. I love your writing, your willingness and ability to bare (and share) those niggles and doubts. Muito obrigado.

As always I enjoy your writing. This line particularly: "From August of 2020 to April of 2021, Filha’s classroom was a collection of pixels." I am happy to hear she is on her way.