When you google “Museum of Resistance,” you’ll find the Museu do Aljube in Lisbon. The small three-story building sits just across Rua Augusto Rosa from the Sé Cathedral. Hordes of tourists pass by it daily in search of a ceramic bauble or scenic overlook. They don’t really notice the plain white building.

It’s not the kind of place that wants to attract attention. In previous lives it was a prison: Cadeia do Aljube. Cadeia as in prison. Aljube as in hole.*

It is said that the building, or some prior incarnation of it, has been a prison all the way back to the 12th century. Once the Muslims were driven out of Lisbon and the Catholics took over, they kept imprisoning people there. Until 1820, Cadeia do Aljube held prisoners of the Catholic church, convicted through the Ecclesiastical Forum—clerics accused of lying under oath, monks who misbehaved, women who used contraceptives. For the next 100 years it caged women who committed common crimes like public intoxication or disturbing the peace.

But the museum doesn’t feature those women or the prisoners who came before them, probably because there isn’t much documentation. But there is plenty of evidence of the stories that the museum does recount—the imprisonment, torture, and murder of the enemies of António de Oliveira Salazar’s Estado Novo.

From 1928 until 1965, political prisoners were held and interrogated within the stone walls of this building. On the third floor you can see their lightless cells, tiny cement boxes called as gavetas: the drawers.

Museu do Aljube is dedicated to the men and women who opposed Portugal’s most recent fascist regime, and “to the history and memory of the fight against the dictatorship and the recognition of resistance in favor of freedom and democracy.”

The museum is a monument to activism. Though the permanent exhibition focuses on the resistance efforts under Salazar’s oppressive regime, other exhibitions have lauded the colonies’ resistance to Portuguese rule, historical resistance to sexual and gender suppression, and the essential role of women in resistance movements.

I spent some time in the museum last week, reading about how spies of the New State were everywhere—your neighbor, your cousin, everyone was watching everyone. Bufos, the informants were called. Squealers. The secrecy surrounding Resistance meetings was elaborate. They met in barns, in kitchens, in wooded areas. People arrived separately, by a variety of avenues, so it wouldn’t look like a crowd was gathering. Someone always kept a lookout, climbing up a tree, peering out a window.

In a time before computers and mobile phones and communication apps of all flavors, the printed word held all the power. Newspapers, flyers, and pamphlets, written up on muffled typewriters because even the noise of the keys clacking was suspicious. Police kept an eye on every store that sold the paper, ink, and stencils necessary to run a printing press. “This equipment,” reads a museum display, “was essential for breaking the world of silence in which Portugal was confined.”

As a word person, this hit me hard. So, too, did the diorama of a woman at a hooded typewriter, fingers just lifting off the keys. “Words matter,” we like to say, and they do. But most of us have never experienced words as a line between life and death.

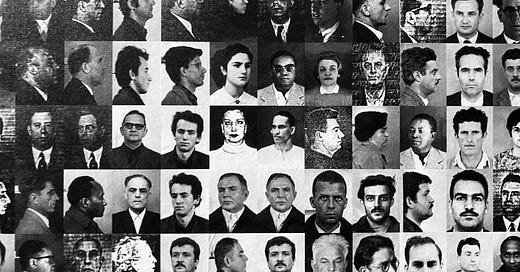

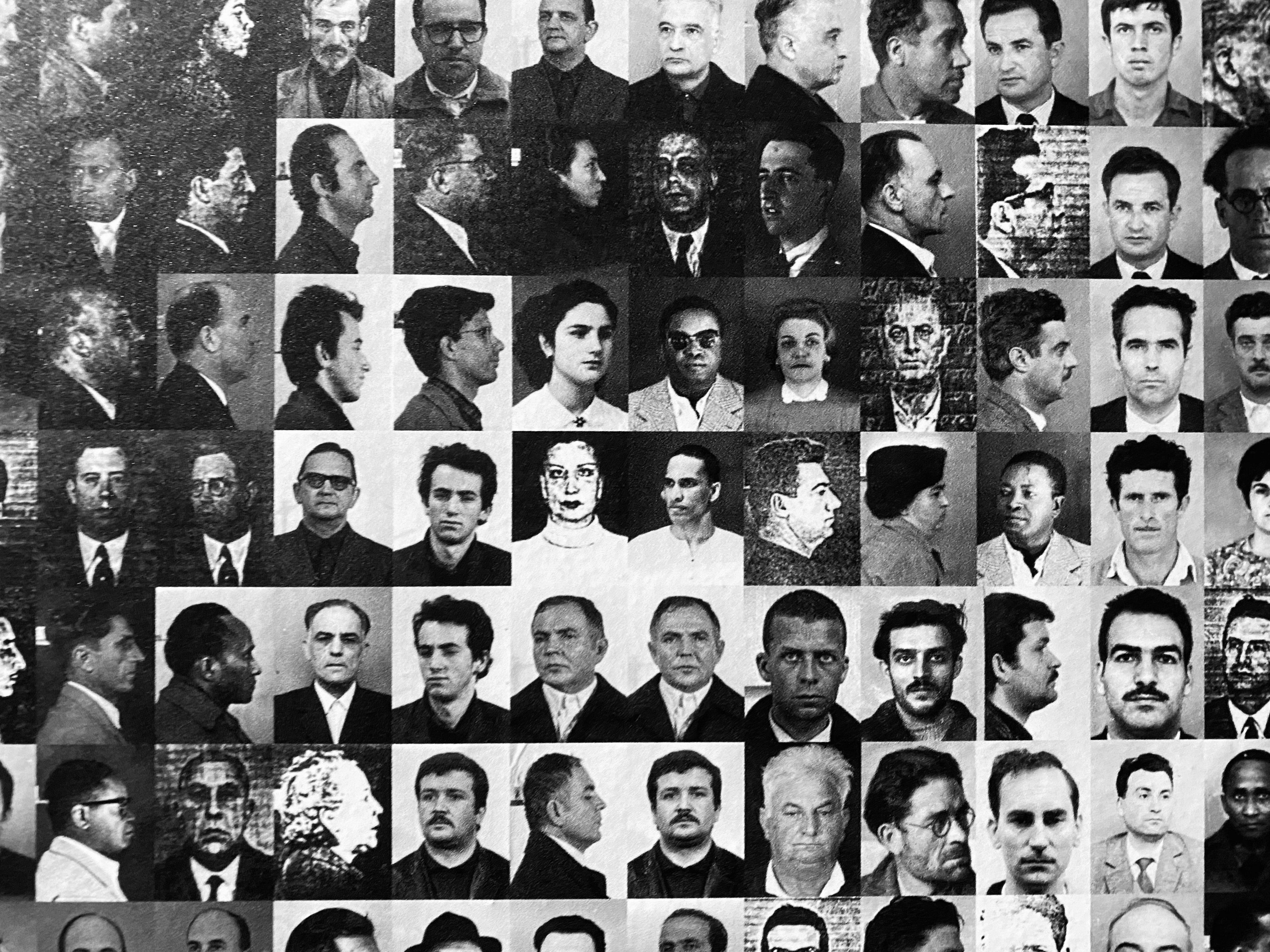

Near the end of your path through the museum, after you’ve walked past the grim row of cells, you’re met with a wall full of black and white photos, small ones the size of a passport photo. The writing on the wall tells you that these are all the men and women who died as a result of their resistance. I stood and stared at their faces for a long while. Eventually I raised my phone and took a photo, the one featured at the top of this entry.

There was nothing particularly special about these people. They were not exceptionally clever or skilled or brave. They were just regular people who looked at the world around them and said, “This isn’t right. I’m going to do something.”

As an American at this moment in time, it’s impossible to walk through the Museu do Aljube without making the very clear connection between Salazar’s reign of tyranny and the regime currently tearing our government apart. An older American couple made their way through the exhibits just a few steps ahead of me. The woman stopped at the wall-sized photo posted above and stared. She looked over her shoulder at her husband, pointed a gnarled finger at the picture and said, “This! This is what is happening right now!”

I’ve been thinking a great deal about the poisoning nature of fear. We see unthinkable things happening and we can’t believe our eyes. We freeze. We hide. We despair. Fear has such power to bind and paralyze. It can batter our imaginations down to mere kernels, so we have nothing left with which to fuel our engines of hope.

Portuguese playwright and novelist Mário de Carvalho said of the Estado Novo:

Fear impregnated the whole social relationship. Fear of being arrested, fear of losing one’s job, fear of social ostracism, fear of persecution and of isolation, fear of calumny, fear of falling into disfavor. Fear of hierarchical superiors, fear of the police, fear of the bureaucrat, fear of one’s neighbors. Fear engendered more fear. For the majority, it was suffocating. There were still people who prospered and felt comfortable in the midst of other people’s misfortune. There still are. And they are still the same.

The everyday people who stood up to Salazar and his henchmen were not scrubbed clean of their fear. They simply chose to act in spite of it. Or because of it. They let it galvanize them into action. A plaque in the museum describes the resistance as “an untamed and untameable opposition that throughout almost a half century never gave up.”

I know a lot of Americans are experiencing a depth of fear and rage in these recent days because they cannot believe what is happening in front of their very eyes. There’s a pervading feeling of “It’s never been this bad before!” accompanied by a steady drumbeat of doom.

Of course, the qualifier is that it has been this bad before, and worse—just not for us white folks.

“If you live in the US and it is the first time you are feeling this scared and unsafe because of the present administration, consider that it is not the first time it’s scary, but instead the first time for you, because of your privilege,” physician and activist named Tanmeet Sethi wrote recently. “Marginalized communities have had a long history of feeling unsafe and threatened. The difference is now systems are dismantling to a degree that affects more people.”

Tanmeet goes on to encourage people not to feel guilty or defensive about their fear or their privilege, but to use this time as a call to join in community. To understand that we are all more connected—and more vulnerable—than we know.

This is a call resounding from so many voices right now, a call to see and hear each other, and to join together in resistance. Not just yelling on the internet about how we’re losing our rights, not just gnashing our teeth at whatever atrocity or buffoonery was enacted today, but actually doing something that matters. (Note: There is a list of real live resistance-style things to do at the end of this post!)

Writer Lidia Yuknavitch calls it a time for “art with teeth” and said in a recent interview, Make Art in the Face of Fuck: I know everybody’s hurting and everybody’s exhausted, but hurt and exhaustion have marked humanity in every epoch. (The way to not) internalize the really supremely fascistic and grotesque and idiotic stories coming at us right now is to stay in community. To keep collaborating; lock arms or fins or tails. And not to say, “I’m going to receive all this terrible shit and take it as mine.” But to say, “This is my time to stand with others.”

Over on Instagram, educator and artist Aleah Black writes about queerness, organizing, blaspheming, and genderfuckery. Last week they shared a powerful message about how to fight this current onslaught of shock & awe that said:

“Chaos requires flexibility and fluidity. Breathe. Let your body move in the currents. You’re not going to drown… This show of force by these pathetic men is to make us forget how many we are. We are so many.”

It’s true. There are so many more of us than there are of them. Some of us are louder and braver. Some of us are legit revolutionaries. But don’t count the regular people out, the people referred to in the photo above as população.

Small amounts of bravery, small acts of resistance, these matter too.

Absolutely, resistance will cost us. On the low end, it costs our time and money. On the high end, our lives. We may not even live to see the results of our labor. Many of the people who resisted Salazar’s Estado Novo never made it to the Carnation Revolution on that April Thursday in 1974.

But we don’t fight for ourselves. We fight because we understand that we are all connected. We speak up because we know we couldn’t live with ourselves if we stayed silent. We stand up because we believe a better world is possible, but it will not come about if we sit idly by. Hope demands action.

Audre Lorde said: “I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.”

Sometimes it’s hard to get started. Sometimes it’s hard to get out from behind your screen. But once you get going, once you raise your hand and open your mouth, it gets easier. And easier. And suddenly you cannot stop. They cannot shut you up.

Even from behind iron bars through the long decades of oppression, the people of Portugal kept fighting. They kept their resistance alive, printed newspapers from prison. They said “down with fear” and made plans for a brighter day.

Even on the saddest night, poet Manuel Alegre wrote,

in times of servitude,

there is always someone who resists.

There is always someone who says no.

Words

A few things to read before and during your acts of resistance…

Be a Revolution by Ijeoma Oluo

The Courage to Disobey by Beth Roy

Audre Lorde: From Silence to Action

Against White Feminism by Rafia Zakaria

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us by Mariam Kaba

Rebecca Nagle on Native Struggle and Survival

Climate Grief: from Coping to Resilience and Action by Shawna Weaver

Actions

A few ideas on where and how to begin and/or continue resisting…

Join collective liberation efforts like Until All of Us Are Free. They provide education as well as helpful action items listed in a downloadable PDF included at the link above.

Give to mutual aid funds and share links to them. Here are three to get you started: For the Gworls, All Our Relations, and The Loveland Foundation.

You can also check out this mutual aid hub for the US.Protect people and animals. Support and advocate for transgender people. Support and advocate for immigrants. Get in the way of the shitheads who work for ICE. Get connected to local activist and community groups so you can find ways to donate your time and resources.

Help the helpers. Not only in times of urgent disaster like fires and floods and front page headlines, but over the months and years that follow. Pick an issue or a disaster or a need that is close to your heart, find the folks who are helping, and commit to supporting them in whatever ways you can for the long haul.

Document what is happening. Who is being helped? Who is not being helped? The PDF I referenced above, provided here by Until All of Us Are Free, has invaluable ideas around documentation and other ways to take action.

*Cadeia means “prison” in Portuguese.

Aljube comes from the Arabic word بّ, “al-jubb,” meaning a cistern or dungeon; a well without water.

One more thing before you go!

There’s an economic boycott happening this Friday, February 28 in the US. All you have to do to join the resistance is: Don’t Buy Anything (unless it’s from a small business and you use cash). Come on ya’ll, this is an easy one. Let’s do it!

If you want to support my work…

You can choose from a couple of tiers of paid subscriptions. In addition to my undying gratitude for your support, you’ll get more of my writing, which is what (I assume) you’re here for! Once a month for paid subscribers only, I will post an excerpt from my memoir-in-progress. The first one is here, for free, if you want a preview.

OR

If you’re not into paid subscriptions, but you’d still like to show support every once in a while, you can leave me a tip via Venmo or Tipeee.

OR

If you want to carry on reading these posts for free because you can’t or shan’t pay, that’s perfectly fine. I do not hide Long Scrawl essays behind a paywall.

NO MATTER WHAT: Thank you for reading. Thank you for telling me when my writing means something to you. That matters most of all.

Copyright © 2025 LaDonna Witmer • {all photos by author, unless otherwise noted}

Many of the conversations about what is happening in the U.S. are just so much pearl-clutching. We need to talk more about concrete acts of resistance that tap into our collective power. Your essay is a terrific call to action. Muito obrigada!

That museum means more to us than all the other museums we have been to in Portugal -- except another Museum of Resistance and Libertation at the former prison in Peniche. We have spent time with a Portuguese man whose parents were secretly in the Resistance. He spoke of the constant danger and how the resisters evaded getting caught.