I am writing from a riad on the edge of the medina in Fès, Morocco, sitting with Filha in a pile of pillows on the blue and green tiled floor. Marido and I have long wanted to visit northern Africa, and when we made plans to move to Portugal, Morocco was one of the countries we pointed to and said, “Look! It’s not that far away at all!”

Much of our first year in Portugal was spent establishing all the logistics of our new lives and routines, and we found ourselves unsettled enough that planning for non-essential travel was overwhelming. But now, 17 months in, it finally felt like time for a vacation. (Plus, I celebrated a milestone birthday a few days ago, and I’m never one to shirk from grand birthday gestures.)

So here we are, two days into a week-long stay in Fés. Yesterday we spent most of the day exploring the labyrinthian alleys of Fes Al Bali, in which even natives of the ancient walled city lose themselves. No wonder, since there are more than 9,400 streets and alleys, 30% of which are dead ends. Nearly all are too narrow for anything but foot (and mule) traffic.

Fès is the oldest imperial city in Morocco, founded 1,200 years ago in 789 by Idrīs I. The ancient medina is now a UNESCO world heritage site and is famous for its bustling souks (markets) and medieval Marinid architecture.

The whole place feels a world away, certainly far removed from everything that’s familiar in the United States, but also from European sensibilities. I think part of this distance can be attributed to the religious underpinnings of our divergent cultures. Even though Portugal looks and feels different from the States, its Catholic infrastructure isn’t all that dissimilar from American Protestant traditions. Our societies might have evolved differently, but they share common roots. Catholic and Protestant are but two sides of the same Christian coin, after all.

Here in Morocco, however, the spiritual currency (and, therefore, the societal structure) is entirely different.

It’s 1:09pm in Fès, and the call to prayer (the second of the day*) begins as a low drone in the distance, swiftly joined by a swarm of other tinny voices. Then the loudspeaker in the minaret closest to our riad clicks on and we hear the lilting cry of the neighborhood muezzin ring out over our heads:

“Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar! Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah. Hayya ala Salat.”

(God is great! God is great! I bear witness that there is no god except the One God. Hurry to prayer.)

When I told my 79-year-old father that we were traveling to Morocco, he said he’d have to look at a map to figure out where that was, exactly. When I told him it was in northern Africa, I could hear the pause and hitch in his breath. “Is it a Muslim country?” he asked tentatively.

My dad is neither well-traveled nor adventurous. He is a gentle soul who prefers the black earth and green cornfields of the Midwest farm towns where he grew up. He made pilgrimages to California once a year for 20 years only because that is where my sister and I migrated and built our lives. He found things to love about California (the Pacific Ocean), even in the big city of San Francisco (he’d ride the N-Judah light rail line from start to finish multiple times during a visit, just for fun).

But he is a meat-and-potatoes sort of guy. A go-to-the-same-restaurant-every-day guy. A wear-denim-overalls-to-church guy. A man for whom the familiar represents safety and the unfamiliar is (increasingly in his later years) cause for alarm.

Even though I have not lived under his roof for 30+ years, he still worries when I travel. Especially when I travel far away. Every time I visit, he asks me to call when my plane touches down so he knows I haven’t crashed and died. And now that he knows my family and I are far from our Portuguese home, he won’t rest well until I call to let him know we’ve returned safely. All wheels on the ground.

Small town mentality plays a part in all of this inherent alarm, but so does religion. Particularly the religious flavor of the sect I grew up in, which viewed even the most devout Catholics as howling infidels.

You don’t want to know what they thought of Muslims.

*There are 5 prayers each day: Fajr (dawn), Dhuhr (midday), Asr (afternoon), Maghrib (sunset), Isha (night).

Although the fear of the other was bred into me, something inside me rebelled from a fairly early age. I began asking questions—the dangerous kind. The breadcrumbs of “Why?” led me up and out and away, and once I was out I just kept going further and further.

I got my first passport when I was 29, and that’s when the world began to open up. Europe was first because it was a safe kind of unfamiliar. An easy introduction. Italy was my gateway drug—the juxtaposition of crumbling ancient ruins sitting cheek-by-jowl next to a Repsol gas station stunned me speechless.

I couldn’t get enough, and soon found my way to employment that would pay for me to travel. I racked up the miles and countries and continents, and then when Filha joined our family in 2010, Marido and I knew we wanted to bring her along on our international adventures.

She got her first passport when she had barely enough hair to hold the yellow plastic barrette I decided was necessary for the occasion.

At age 12, she’s been all over the world, but still hasn’t seen enough of it.

This trip to Morocco is her first time in Africa, her first time in a Muslim country, and I hope it will not be her last. Travel teaches in ways books (much as I love them) cannot. Every trip we take—even our road trips from California to Illinois—open her eyes to new ways of thinking and being.

She gets glimpses of how other people live. Of how different we all can be, how far removed from each other, and yet how often we yearn for the very same things.

Yesterday we passed through a souk where the severed head of a camel hung from a hook in front of a butcher shop. Two stalls over, a clucking white chicken was placed on a scale before meeting a swift end at the skilled hands of a halal butcher.

This was a sudden one-two punch for our tender-hearted animal lover, and she ducked her head behind me, tears in her eyes. “Let’s get out of here, Mom,” she pleaded.

I hadn’t known where our guide would take us or what to expect from the souks that day, so I was just as surprised by the carnage as she was. But also, I grew up on a farm and have seen animals die for food.

Filha took some time to recover, and the event sparked multiple conversations throughout the day. We talked about how, in the States, death is hidden away. You might know that an animal died for your dinner, but the meal arrived pre-packaged and free of all the blood and mess. You don’t hear a chicken squawk its last before turning into nuggets.

We talked about her best friend who is vegetarian, and all the reasons for choosing that lifestyle. We talked about animal care and cruelty. We talked about farms and all the complications of treating animals as livestock.

We talked about how she might never eat chicken again.

Would I have chosen to walk through that particular souk, knowing what she’d see?

It’s not like I am going to blithely answer: “Yes, I want my kid to see hard things.” And yet I don’t want to be her bulldozer mom or her shit umbrella, either.

If travel is going to teach us something, we can’t expect it to always be comfortable.

We talked about that discomfort, too. She shed some tears over missing her best parrot friend (FeeBea is very happily being birdsat by our friends Ken & Jo.) She shed tears over the hapless white hen now braising in a tajine somewhere. She said she was homesick for Portugal.

“It’s normal to be homesick when you travel,” I told her. “Some of the most amazing places I’ve traveled were also the hardest trips. Sometimes I cried because I saw something sad. Sometimes I cried because I missed being at home. That’s ok. Traveling, especially traveling far away from everything you know, is a mixture of these moments of absolute wonder with other moments of being really tired or hot or having blisters on your feet, or not being sure what is going on because everything and everyone is so strange to you. But then, when you look back at the trip, you’re so glad you went and did that and saw that and met those people. Because you never would have had those moments of wonder if you just stayed home.”

These conversations are a gift I’m glad to give.

Tomorrow, we’re taking a day trip to Chefchaouen. It’s going to be a long car ride, and I imagine a portion of the day will be decidedly uncomfortable. But that’s not the part I’m choosing to focus on.

I’m looking forward to those moments of wonder. To seeing sights I’ve thus far only experienced through pictures. And to talking about what we’ve seen and learned, on the way home.

Meanwhile, there’s still daylight left here. We’ve got to get out of the riad and into the heart of Fes Al Bali again. Filha’s been counting medina cats. Yesterday she saw a record number: 121. Who knows how many she’ll see today (inshallah).

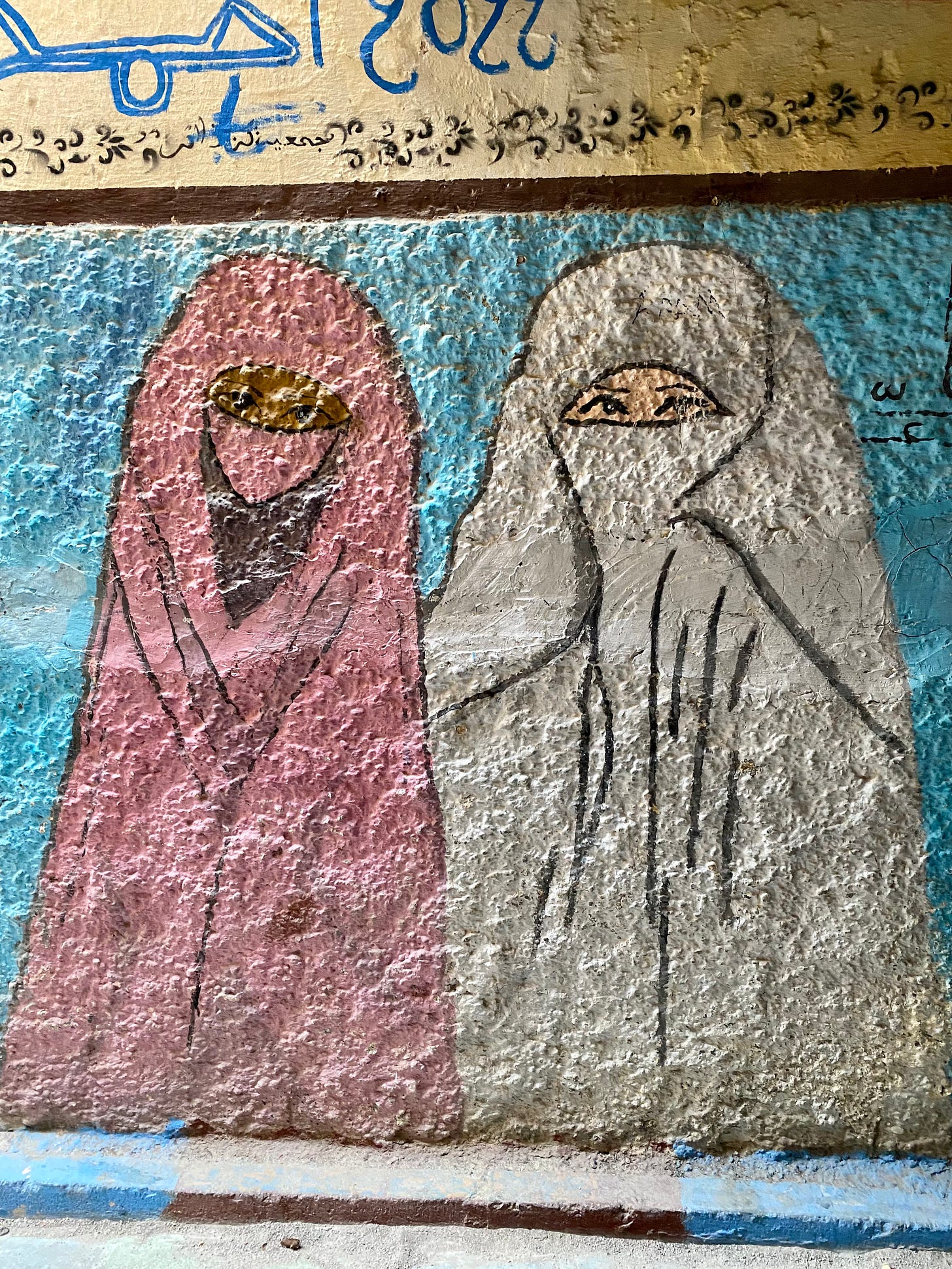

Bonus Fès Photos:

Copyright © 2022 LaDonna Witmer

Aside from your unique travelogue, your piece resonates for me as an ode to healthy and conscious parenting ... inviting life to unfold organically for your little one and receiving her heartfelt questions with grace and presence. And importantly, reassuring her that all emotions are welcome and meant to be felt. As an emotions therapist who works with adults looking to be in touch with their "difficult" emotions, I admire your commitment to showing your daughter in her childhood how to embrace the richness of everything she's feeling.

You inspire me. You inspire me, to write more and to try and improve my words, the words I string together. You inspire me. You inspire me to follow - in your footsteps. To travel more. To be uncomfortable and to embrace that. I feel your words. You photography is wonderful, but your words paint a picture. Your words lead me to wonder, with you. Your words let me know - that I am not - alone. (Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.)